One of the largest underwater avalanches in Earth's History mapped from head to toe

New research by the Aarhus University has mapped of the world's largest underwater avalanches off the coast of Morocco, from source to sink and decodes its trail of destruction

Avalanches don not only happen in snow-covered mountains. They also occur underwater, and they can quickly grow from small landslides into massive avalanches that transport enormous amounts of sediment. In a study published in the journal Science Advances, researchers provide an unprecedented insight into the scale, force and impact of one of nature’s mysterious phenomena, underwater avalanches.

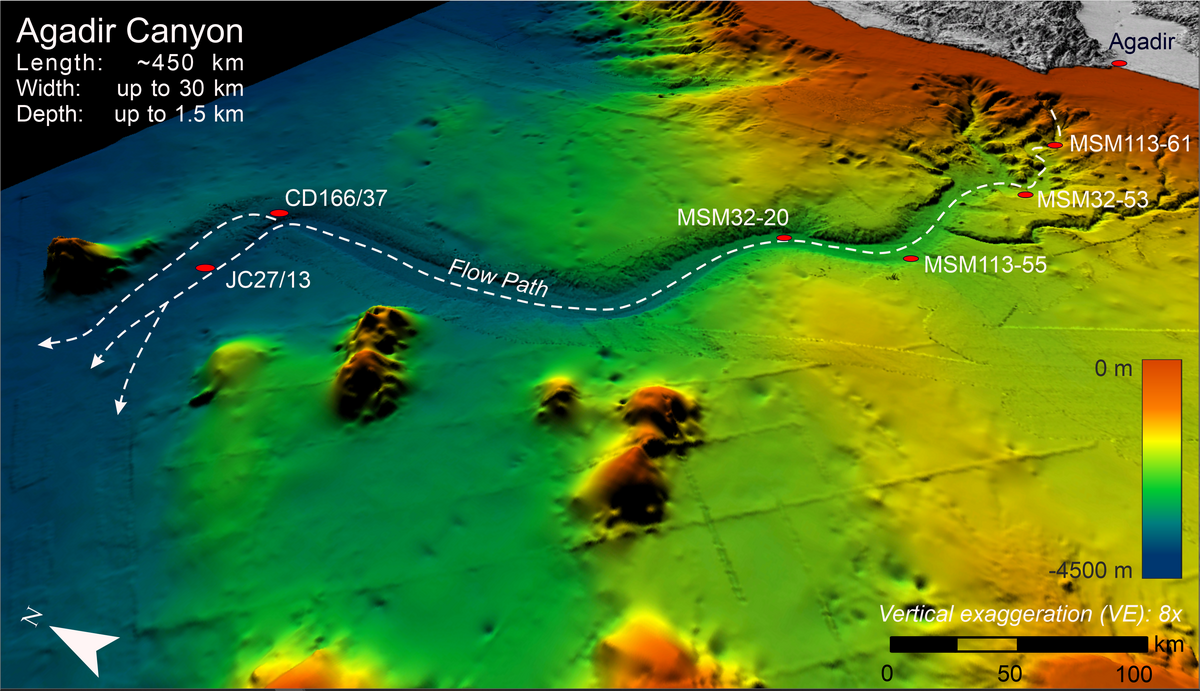

Dr. Christoph Böttner, a geophysicist from Aarhus University, co-led the team that for the first time mapped the Bed-5 underwater avalanche that happened about 60.000 years ago from head to toe. The event began as a small landslide in the Agadir Canyon off the coast of Morocco. On the way through the canyon, the small event grew a hundred times its size and left a trail of destruction as it travelled 2000 km across the Atlantic Ocean seafloor off the Northwest coast of Africa.

A Destructive Journey

In the paper "Extreme erosion and bulking in a giant submarine gravity flow" published in the journal Science Advances, a group of international researchers provides an unprecedented insight into the scale, power, and impact of one of the largest underwater avalanches in world history, known as the Bed 5 event. The research is a collaboration between scientists from the Universities of Kiel, Aarhus and Liverpool, together with colleagues from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel and the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW) in Germany.

Using more than 300 sediment cores collected over 40 years, along with seismic and bathymetric data collected on two research cruises to the Moroccan coast in the last ten years, the researchers can now trace the destructive avalanche's journey through one of the largest underwater canyons in the world, covering a distance equivalent to the journey from Aarhus to Rome. An enormous mass of sediment, as tall as a modern skyscraper, swept across the seafloor at 50-60 km per hour, destroying everything in its path and thereby burying an area of the size of Germany.

Bed-5 is an example of how a relatively small event can grow into an extreme flow because it picked up such large amounts of sediment. This is the first time anyone has been able to follow the destructive trail of an underwater avalanche from start to finish and calculate its growth factor.

Threat to Modern Society

In contrast to a landslide on land or snow avalanche, underwater avalanches are impossible to see and extremely difficult to measure. However, they are the primary mechanism for moving materials like sediments, nutrients, and pollutants across the Earth's surface and represent a significant geohazard that threaten marine infrastructure.

The understanding of the Bed 5 event fundamentally changes the way we view underwater avalanches. Before the study, it was believed that large underwater avalanches originated from appropriately large slope failures (marine landslides). Now we know that they can start as small events that, under the right conditions, can grow more than a hundred times their original size to immense volumes. This is important for better predicting potential geohazards and assessing their possible impacts on maritime infrastructure and ecosystems. The forces at play are immense, and once an underwater avalanche is set in motion, the massive forces can easily destroy all cables in its path, potentially cutting off entire continents from the internet that our modern society so heavily relies on.

And read more about the paper on Kiel University’s webpage or on University of Liverpool’s webpage.